The following article appeared in the New York Times in August 2006. Some archival photos have been added.

Streetscapes | West 81st Street By Christopher Gray.

A Roller-Coaster Ride of Styles

WEST 81ST STREET, between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues, zooms uphill and then down like a thrill ride at Coney Island. Its combination of extreme topography, clashing colors and colliding architectural styles makes it a particularly memorable block.

Notable architectural details of the block include the basket balcony at No. 135 (above).

Start on the north side, just in from Columbus, and head west. The frantically varied first row, Nos. 117 to 133, was built from 1884 to 1888, mostly by Samuel Colcord, a prominent West Side builder known as Lucky Sam. He had given up the ministry for real estate after a doctor advised him to take up an outdoor occupation. With the fortune he made from his row houses, he became a well-known peace advocate after World War I.

His architect, Henry Harris, strove mightily to present a variegated front to the street, each house different from its neighbor in some way. The house at 127, for instance, has downright ornery door and window framing, with ungainly blocks of stone placed at odd intervals.

At the same time, Mr. Harris experimented with large-scale effects, as seen at 129 and 131. He joined them under a single gable, not to make them look like one house, but simply to avoid the “marching soldier” effect common to brownstone rows. Jerry Seinfeld had an apartment at 129 West 81st around 1980.

The 1946 photograph above shows the Wesley apartments at No. 158.

Just past the crest of the block stands a most unusual house, No. 135, designed in 1886 by H. Edward Ficken, a Scottish-trained architect. Painted cream, this is the one with the bold basketlike iron balcony and bottle-end green glass portholes in the oak door. To a 21st-century eye the strap work suggests the Tudor style, and the usual tag is Queen Anne, but really this house, like many 19th-century row houses, is unclassifiable. In the 1890’s, it was the home of Remigio Loforte, a decorator, well known at the time, who worked with McKim, Mead & White.

The next row, 137 through 143, designed in 1886 by Rossiter & Wright, speeds dizzyingly downhill. The firm made its row a circus sideshow of architectural forms: stumpy little columns, strangely placed keystones and angled bays alongside traditional decoration like the egg-and-dart motif.

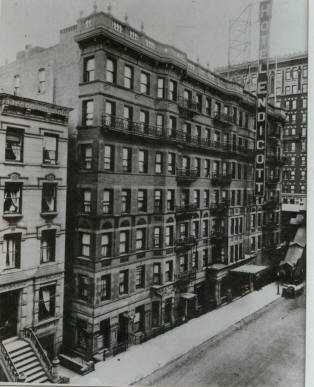

Above the elevated railway station stop on Columbus Avenue at 81st Street with the Endicott behind.

That the houses have since been painted in different colors — like the peculiar olive of 139 — only adds to their weird charm. “Exceptionally vivacious,” said Robert A. M. Stern, Thomas Mellins and David Fishman in their book, “New York 1880” (Monacelli, 1999).

The piquantly modernist apartment house at 155 West 81st, built in 1945 and designed by H. I. Feldman and Herbert Lilien, has some moderne porthole-style decoration, but its most important function is the struggling garden in front, which gives a little relief on this traffic-laden street, a main route to Central Park.

Across the street on the south side of the block and back toward Columbus, the Wesley, a 1913 apartment house by Neville & Bagge, stands at No. 158 West 81st. In its vestibule are rich luminescent panels, maybe onyx, in green, gray and white with spidery red veins.

On one wall a jagged rectangular hole, perhaps the site of long-gone mailboxes, has been patched with a naked scar of white plaster, refreshingly innocent of any faux painting or other cosmetic fixes.

The church next door, built in 1892 for the Third Universalist Society, has a peculiar rocky front, designed by John F. Capen. Under the arcade, the opposing stairways, set as they are on the steep slant of the street, further emphasize the block’s vertiginous character.

Don’t miss the 1888 house at No. 136, designed by Thom & Wilson. It has some of the most fanciful brownstone carving you’re ever likely to see. Above the window is a winged head with a fruit vine coming out of its mouth, and on either side of the doorway, two lions hold something resembling large balls of mozzarella in their mouths.

Mr. Colcord, the builder, also active on this side of the street, constructed the four houses at 116 through 122. In 1911, as the block’s private-house bloom was fading, the Interborough Suffrage Club leased No. 120 for meetings and other activities. The New York Times noted tongue-in-cheek that its cafe offered “red-hot suffrage beverages” in the winter and in the summer, cold meals “as frigid as the attitude of some politicians” to the cause of voting rights for women. (Below the Endicott at the end of the 19th century)

Above, the Endicott apartment building with an exit from the elevated line.

At No. 110, brownstone repairs are under way, perfectly demonstrating the fickle nature of that vexatious material. A panel underneath the window was originally set with the sedimentary beds oriented vertically, facing the street, and it is no surprise that they gradually peeled off. But the free-standing column at the corner has the beds set parallel to the ground, and they are in near perfect condition, showing the richness and complexity of the stone, despite the deep carving.

Perhaps the most wonderful thing on 81st Street between Columbus and Amsterdam is not architectural but botanical: the colossal wisteria vine running up the front of the Rossiter & Wright house at 143. It spreads to both edges of the facade and then goes over the top, a green monster that has nearly swallowed the building, now a co-op.

“I call it ‘God’s ribbon,’ ” said R. Couri Hay, the publicist and writer who has lived there for about 30 years. “It’s been my calling to protect that vine.”

Mr. Hay said he had foiled attempts to remove the vine, which has four intertwined trunks so muscular and gnarly that they seem like the serpents that strangled Laocoön and his sons in Virgil’s “Aeneid.” So fast does it grow that Mr. Hay said the co-op will have to spend $5,000 for trimming it this year.

“It’s like having a pet,” he said.

************************************************************

New York Times. June 15, 2008

Urban Studies | Miniaturizing

Welcoming a Car You Can Park on a Dime By CAROLINE H. DWORIN

NESTLED between an enormous Mitsubishi and a sprawling Jeep Liberty, the tiny red Smart car sits like a nub of jam between two slabs of cake. A stump of an automobile, a squat, friendly two-seater less than nine feet long, it fits, fuel-efficiently, in the half-spaces outside its owners’ apartment building on West 81st Street near Columbus Avenue.

Produced not by Fisher-Price or Tonka, but by Daimler, the Smart car seems suited to an island where square footage is everything, and dogs and cats often weigh about the same. George Bastuba (6 feet tall), an information technology manager, and his wife Nori Akashi (5 feet 2), a photojournalist, bought this one in March for $13,000, with $99 down.

“No bells or whistles,” Mr. Bastuba said. “No automatic windows. You just don’t need them. You can roll down both at once without shifting in your seat.”

Two passengers can ride together, though no more. And groceries fit, as do golf bags, two of them, if you remove and readjust the woods.

The Smart car is still a bit of an anomaly, like a hummingbird sighting in Central Park. There are about 300 on the road in the region since the car’s arrival in the United States in January, a decade after its successful European debut, according to Ken Kettenbeil, Smart’s communications director.Smart Car

People honk, or give thumbs up, and sometimes raise their camera phones while driving by. Cabdrivers seem especially moved, as do children who point and stare. “What is that?” one city bus driver asked, staring down at the little car from her perch.

Mr. Bastuba said that when one is flying down the West Side Highway at 80 miles an hour, it is easy to forget how small the car is — as if speeding along in the cab of a pickup. “And you get out, and turn around, and think: ‘Wow! Where’s the rest of it?’ “ On a recent drive to Washington, the couple estimated, the car got nearly 50 miles per gallon on the highway, and 42 in traffic (a number likely aided by a stiff breeze at their back).

On a recent morning, the nub-nosed car on 81st Street, with the diminutive geometry of a red M&M, basked in the attention of passers-by. A Mini Cooper owner rapped on its body and measured its length with his arms. “Plastic,” he scoffed.

Despite the fact that a Smart car driver may feel every blacktop inconsistency through his or her spine and dental fillings, there is something irrefutably endearing about this vehicle. It demands so little; and one finds oneself almost protective of it, as if it were a quirky younger sibling.

Nicole Celichowski, and her husband, Matt, returning the other day to visit the city from their new home in Minnesota, slowed on the sidewalk as they passed the Smart car with their infant and toddler. “Look, it’s like your Cozy Coupe!” Ms. Celichowski said as she pointed to the vehicle resembling her daughter’s toy car. “Only that has pedals.”

![13scape1948[1].6](https://www.w81blockassoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/13scape19481.6.jpg)